Are you using the right encoders to capture and deliver your live and on-demand video?

There are two categories of video encoders: File Encoders and Streaming Encoders.

File Encoders

File Encoders seek to make a compressed video file that can be delivered from physical media or over a network. A file encoder uses a uncompressed video file as an input and produces a compressed video file. When a file is processed, File Encoders can analyze the entire input file, frame-by-frame, and use multi-pass techniques to produce an output that is highly optimized. They can use time to apply various pre-processing “tricks” (such as noise reduction, color optimization, deinterlacing, etc.) to ensure the output is as good as possible. These encoders are often less than real time, where it takes longer than 1 hour to process a 1-hour video.

File encoders are typically included in video authoring/editing tools, such as Final Cut, Vegas, Media Studio, and Premier, and are invoked when you select “Render” or “Save-As”.

A file encoder is what is used by Hollywood studios to make DVDs and BluRay disks, and by NetFlix and similar providers to create files at various bit rates and resolutions.

Stream Encoders

Stream encoders seek to make a compressed video stream that can be delivered live over a network. A stream encoder uses a live video input, such as a HDMI or SDI feed. Because a live encoder must produce the compressed video immediately, there is little opportunity for quality improvement. That is, multi-pass encoding techniques are not possible.

Live encoders may try to improve quality by conducting deinterlacing and some noise reduction of the input, but generally the quality of the output is more reliant on the quality of the input and the compressing technique (i.e. the quality of the H264 encoder itself and the settings used). Stream Encoders may also record, where the live stream is saved locally. The quality of the recording can be excellent, but would not be as good as those produced by a File Encoder which can perform quality improvement “tricks”. For most use cases, the difference may not be visible, especially when the Stream Encoder can record at different settings then used for live streaming. Unlike a File Encoder, rate control is more important. For a file, during periods of high motion you can maintain quality by increasing the bit rate. But for a streaming encoder that is trying to maintain a constant bit rate, you have to apply backpressure to the encoder and there are many techniques for this. So a Stream Encoder is more complex. To answer the question “Which produces a quality video?”, the answer would have to be a File Encoder. To answer the question “Which produces a better stream?”, the answer is only a stream encoder.

A stream encoder is what is used by live services such as Sling and similar “Live TV” providers, often at various bit rates. All DiscoverVideo encoders are stream encoders.

Compression

You will want to use H.264 video compression (A.K.A. MPEG-4 Part 10). Next-generation compression H.265 does not provide much improvement for streaming at the bit rates of interest for most people (at very high data rates and for commercial producers it has real value). While other codecs have their advantages, H.264 is supported on virtually all platforms (browsers, mobile devices, set top boxes, Roku receivers, Samsung TV’s, etc.).

Like anything else, you can have poor H.264 and good H.264. What makes it good? Well, it’s a bit technical, but comparing things like rate control, motion estimation, and processing requirements will give you a good idea of the encoder quality. A compressed video of a non-moving image will look pretty much the same from virtually any encoder. But at any given bit rate, and with the “knobs” twisted to the right values, the differences begin to appear. How blocky is the video? How much CPU is needed? Simply put, not all H.264 video encoders are created equal.

Hardware Appliance vs. Software

Back in 1997 I founded a company to create the world’s first video appliance. It used MPEG-1 and delivered live video over ATM and Ethernet/IP. It was a great success and was followed by MPEG-2, MPEG-4, Windows Media, and H.264 appliances, launching a whole new industry. Today there are many video appliances. However, the motivation for hardware-based vs. software-based encoders has changed.

It was almost laughable to expect a circa 1997 x286-based CPU running Windows 95 to be a reliable platform for video streaming. Machines in those days could barely play a video, let alone create one. When 3rd party cards began to appear the PC could actually do some useful video things. But not for long before the infamous blue-screen-of-death would appear. An appliance, however, is engineered specifically for video encoding. Using dedicated chipsets, it can be made to be reliable, compact, and purposeful. It does not relay on a general-purpose CPU for encoding, but uses video compression chips and optimized D/A input devices.

We have come a long way since the the first video appliance. Today we have more computing power on our phones than the astronauts had to land on the moon. Encoding video on a universal computer platform is today perfectly reasonable, and there are many software video encoders for Windows and Apple computers. Software encoders can take advantage of Intel or Nvidia technologies to lower the CPU load and produce video of the same quality that used to be only the domain of video appliances. Of course, a computer does not come with any video inputs…except for maybe a built-in webcam. To bring in video sources, you need a USB device (RAZOR) or a capture card (Captiva).

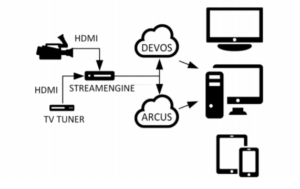

All video encoders use software. Many of the popular 3rd party encoders use the Windows operating system even though it is not exposed to the user. Hardware-based encoders, however, use dedicated chips (DSPs) to perform the actual video encoding. Using dedicated hardware in a multi-channel encoder allows high channel density and lower per-channel cost. DV StreamEngine, for example, can encode up to 12 simultaneous video inputs and both stream and record the content in HD H.264.

How To Choose Video Encoders

- For occasional use (e.g. daily 30-minute broadcast), a desktop software video encoder is ideal, provided your computer has the horsepower necessary (think Core i7 class machine).

- Add the cost of your computer (e.g. $1000) to the cost of the software plus the cost of the capture device (USB or PCIe card), and you may find that using a PC as a dedicated video encoder is more expensive than an appliance.

- Use a video encoder appliance for continuous streaming, as is done for IPTV applications.

- Use a video encoder appliance to get an “Easy Button”, and when the size and complexity of a PC is simply not warranted.

- For 360-degree video, use a dedicated 360-degree camera that has built-in streaming and file encoders.

DiscoverVideo Video Encoder Selection Guide

As I mentioned, DiscoverVideo makes several streaming video encoders, and this comparison guide should help with your tool selection.

Still Need Help?

If you’ve read this all the way through and would like further guidance for your business, school or offices, please get in touch with me, Rich Mavrogeanes at (203) 626-5267.